The Wonder of Woodland SavannahsBy Shawn Head

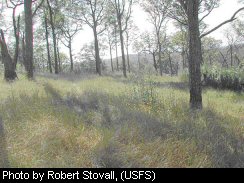

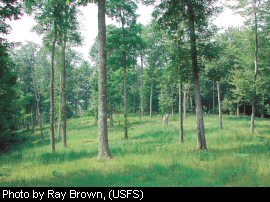

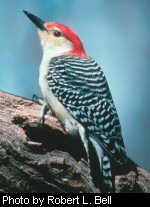

Savannahs represent one of the most unique and productive types of wildlife habitat we have on public lands in West Virginia. They are different from the traditional small herbaceous wildlife clearings. Savannahs are best described as grassy openings or clearings with scattered mature trees, including snags and den trees, surrounded by forest. As a type of wildlife opening, they may be maintained by annual or rotational mowing or by prescribed burning. Placement is one of the most important criteria in developing savannahs . West Virginia does not have a large component of flat lands or gently rolling hills. As a result, savannahs are usually placed on ridge tops or on the gentle slopes just off ridge tops. More opportunities to develop savannahs exist on private lands because more suitable terrain normally occurs there than on public lands. Since our prevailing weather generally comes from the west or southwest, many savannahs are developed on the lee side of ridges, sloping toward the east or northeast. This has a buffering effect from prevailing winds and storms, which can cause occasional windfall of mature trees. Remoteness is another important criteria in savannah development. Remote areas are characterized as areas away from roads and human disturbance and within large tracts of forestland usually void of clearings and natural openings. Research has shown that savannahs developed in remote, forested habitat are extremely beneficial and used more readily than clearings by wildlife species, including the wild turkey. The West Virginia Division of Natural Resources embarked on a Wild Turkey Population Dynamics Study from 1989 to1994, to study the survival of wild turkey hens throughout the state. While tracking these radio-harnessed birds, it became The residual trees left standing are usually a combination of oaks, hickories, black cherry, American beech and white pine. Depending on forest type, aspect and elevation, residual trees could also include sugar maple, red maple, ash or yellow poplar. Leaving snags and den trees (cavity trees) for use by wildlife also adds value to savannahs . In areas that have a mixed oak/hickory and pine component, island clumps of pine trees should be left standing for roosting and nesting sites. If feasible, at least one water hole should be constructed in conjunction with the development of a savannah . Standing water sources, extremely valuable to area wildlife, often don't exist on ridge tops. Many species use water holes, including frogs, salamanders, turtles, songbirds, herons, raccoon, wild turkey and deer. Forest succession usually progresses through four stages: herbaceous (grass and forbs ), shrub and sapling, pole timber, and mature timber. Savannahs uniquely include both herbaceous and mature forest stages of forest succession. These two successional stages, existing simultaneously on the same acreage, act as a magnet to attract a diversity of wildlife. Savannahs are also unique in that they contribute to increased biodiversity within a regional landscape, adding important habitat diversity and species diversity to a forest ecosystem. Undoubtedly, they add an important recreational advantage, because savannahs make great wildlife viewing areas, attracting everything from butterflies to black bears. Savannah DevelopmentWhen choosing potential sites, savannahs should be located on level ground or slopes less than 10 percent. Size is dependent upon wildlife habitat objectives and the availability of suitable lands, but savannahs normally range from 5 to 20 acres. Once a site has been chosen, the boundary is marked and residual trees that are to remain are flagged. A 50- to 60-foot spacing between trees should be maintained. The location of any temporary logging roads or skid trails for timber removal should be laid out. Once residual trees are flagged, all remaining trees should be cut and removed. Slash from treetops and any other woody ground debris should be removed and placed in piles distributed throughout the savannah . All tree stumps Two recent savannahs completed on the Monongahela National Forest involved digging up stumps less than 24 inches in diameter, while larger stumps were ground down below the soil surface. Once all woody debris and stumps are placed in the dispersed debris piles, the area should be smoothed over by bulldozer and root rake, in preparation for lime and fertilizer application. Soil preparation is very important. Soil test kits, available from the Natural Resource Conservation Service, Farm Service Agency and the WVU County Extension Service, can be used to determine appropriate lime and fertilizer application rates. Once lime and fertilizer have been applied, a mixture of grasses and legumes is seeded and lightly disked. Seed mixtures may include both cool season and warm season grasses with one or more legumes. Successful seed mixtures have included combinations of annual ryegrass, perennial ryegrass, redtop , timothy, orchard grass, birdsfoot trefoil, ladino clover and partridge pea. Specific species that also grow well in savannahs include bush clover, bundle flower, black-eyed Susan, oxeye sunflower, downy sunflower, big bluestem , Indian grass and switch grass. Once the herbaceous understory is established, it is possible to plant wildlife fruit trees and shrubs including apple, crabapple, chinquapin, hawthorn and border or clump-plantings of pine or spruce. Wildlife fruit trees and shrubs may be protected by tube shelters and by planting them at the edge or just inside the edge of the dispersed debris piles. This has shown to provide some degree of protection from deer and black bear. In conclusion, savannahs are not only unique — they are multi-purpose in design. Savannahs are a living, functioning microcosm of interacting habitat types on the same acreage. These habitats include critical herbaceous understory essential to productive brood habitat for wild turkeys and ruffed grouse. The mature hardwood mast In the edges of savannahs and in the dispersed debris piles, pokeweed and blackberry thickets may establish naturally. The established grasses provide ideal hiding cover for fawns. Many species of wildlife use snag and den trees for foraging, foraging perches, singing perches, nesting, escape, cover and courtship displays. If you have the opportunity, I welcome you to spend part of a day in one of the developed savannahs we have on our public lands throughout West Virginia. For more specific information on savannah development, please contact any DNR District Office or the Elkins Operation Center at 1-304-637-0245. Shawn Head is a wildlife biologist stationed in Elkins. |

When I saw my first savannah in 1990 on the Monongahela National Forest, I was amazed not only by its size but how good it looked as functional wildlife habitat. While hunting this same area in the fall, I found the amount and kinds of wildlife that were using it even more amazing.

When I saw my first savannah in 1990 on the Monongahela National Forest, I was amazed not only by its size but how good it looked as functional wildlife habitat. While hunting this same area in the fall, I found the amount and kinds of wildlife that were using it even more amazing.  apparent that turkey hens and poults heavily used remote savannahs and savannah -type habitats during the late spring and summer months.

apparent that turkey hens and poults heavily used remote savannahs and savannah -type habitats during the late spring and summer months.  should be either removed to debris piles or ground down to six inches below the surface with a stump grinder.

should be either removed to debris piles or ground down to six inches below the surface with a stump grinder.  trees produce important fall and winter foods such as acorns, hickory nuts, walnuts, beechnuts and black cherries. Piling debris throughout the savannah and around boundary edges provides excellent cover for small game and nongame wildlife.

trees produce important fall and winter foods such as acorns, hickory nuts, walnuts, beechnuts and black cherries. Piling debris throughout the savannah and around boundary edges provides excellent cover for small game and nongame wildlife.