Out of Sight, Out of Mind By James Walker and Jim Hedrick The study of the physical, chemical and biological characteristics of freshwater environments is known as limnology. Biological communities in lakes respond in a predictable way to changes in the environment including variations in temperature, light and a host of chemicals in the water. Let’s explore a few of the critical factors to gain a greater understanding of what goes on under the surface of our West Virginia waters. Lake changes occur seasonally and can have a major impact on fish distribution, feeding, activity and ultimately your fishing success. Knowledge of the lake environment can help anglers tailor their fishing gear and techniques to improve fishing success on every trip. A major factor affecting fish distribution and feeding during the

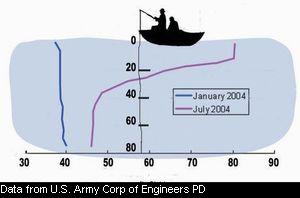

summer is lake Stratification occurs throughout the summer and early fall as warm water rises to the surface while the cooler water sinks to the bottom of the lake. This happens because cooler water is denser than warm water. The water will separate into distinct vertical layers of different temperatures. Lakes commonly stratify into three layers know as the epilimnion,

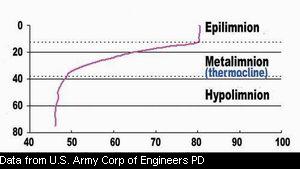

metalimnion and hypolimnion. The epilimnion is the upper layer of

water in which the water In West Virginia , many reservoirs and small impoundments commonly stratify between May and October. The extent and duration of stratification depends on the size, shape and depth of the lake. Some reservoirs may not stratify like natural lakes due to the release of cold water through the bottom of the dam. Fish survival is dependent upon an adequate supply of oxygen in

the water. Oxygen enters the water through contact with the air or

it may be released by aquatic plants. Stratification and dissolved oxygen affects fish distribution and ultimately fishing success. During hot summer months many fish species seek cool water in the lower water column. Many anglers target these cool water areas with deep diving lures and baits. However, many anglers may not be aware of other important aspects of stratification. Due to the natural process of decomposition and decay of organic material including leaves, logs and microscopic organisms, oxygen can become depleted in the hypolimnion. Although cool water is capable of holding more oxygen than warm water, the hypolimnion does not mix with the upper layers and oxygen cannot be replenished. Despite the cool water that would typically attract many fish species, the lack of oxygen will prevent fish from occupying this area. Some small impoundments in West Virginia may only have oxygen in the top two layers of water. Therefore, fishing deep water will yield few, if any, fish. In the fall, water temperature begins to decrease in the epilimnion

and the cooler water sinks. Wind creates waves and adds to the stirring

action. As the water temperature becomes more uniform from surface

to bottom the entire lake will begin to circulate once more. The

return of circulation throughout the entire water column is known

as fall turnover. Following fall turnover and throughout the winter

the water temperature is nearly consistent from the water surface

to the bottom (see graph below).

Fish kills can be associated with fall turnover. If oxygen levels become low in a large portion of the lake during the summer due to decay of organic material, fall turnover can result in extremely low oxygen levels throughout the entire water column causing fish to die. Fish kills as a result of fall turnover commonly occur in farm ponds. If farms pond are 10 to 15 feet deep or deeper, they may have summer stratification. A single weather event like a thunderstorm may cool the surface water, cause turnover and result in low oxygen. Future issues of West Virginia Wildlife will examine how microscopic organisms and nutrients determine the number and size of fish a lake or pond can support. Jim Hedrick is a fisheries biologist stationed in Farmington . James Walker is a fisheries biologist stationed in French Creek.

|

stratification. In winter and spring, lake water temperature

is uniform from top to bottom and the entire body of water circulates

very slowly. This water circulation replenishes oxygen in the bottom

of the lake and brings nutrients up from the sediments.

stratification. In winter and spring, lake water temperature

is uniform from top to bottom and the entire body of water circulates

very slowly. This water circulation replenishes oxygen in the bottom

of the lake and brings nutrients up from the sediments.  temperature is uniform and in which the

water circulates due to wind and wave action. The hypolimnion is

the bottom layer of water, characterized by cold water that no longer

mixes with the warm, upper layers of water. The metalimnion is the

middle layer of transition between the warm and cool water. The zone

in which there is a rapid drop in temperature is known as the thermocline.

Slight variations in the depth of the thermocline may exist in one

lake due to other factors. If you have ever been swimming in a lake

during the summer and felt much colder water on your feet, you have

hit the thermocline. The graph below of water temperature at various

depths in Stonewall Jackson Reservoir during July 2004 clearly illustrates

lake stratification.

temperature is uniform and in which the

water circulates due to wind and wave action. The hypolimnion is

the bottom layer of water, characterized by cold water that no longer

mixes with the warm, upper layers of water. The metalimnion is the

middle layer of transition between the warm and cool water. The zone

in which there is a rapid drop in temperature is known as the thermocline.

Slight variations in the depth of the thermocline may exist in one

lake due to other factors. If you have ever been swimming in a lake

during the summer and felt much colder water on your feet, you have

hit the thermocline. The graph below of water temperature at various

depths in Stonewall Jackson Reservoir during July 2004 clearly illustrates

lake stratification.  The amount of oxygen present

in water depends primarily on temperature because cooler water holds

more oxygen. Coldwater species such as trout require high levels

of dissolved oxygen. For this reason, we find trout primarily in

headwater streams where the water is cold all year and the churning

action of water as it flows over rock increases the oxygen content

of the water. Coldwater fish may survive in lakes, small impoundments

and farm ponds during winter months when the water is cold. However,

as water temperatures rise with approaching summer, available oxygen

will decrease and species like trout may not survive.

The amount of oxygen present

in water depends primarily on temperature because cooler water holds

more oxygen. Coldwater species such as trout require high levels

of dissolved oxygen. For this reason, we find trout primarily in

headwater streams where the water is cold all year and the churning

action of water as it flows over rock increases the oxygen content

of the water. Coldwater fish may survive in lakes, small impoundments

and farm ponds during winter months when the water is cold. However,

as water temperatures rise with approaching summer, available oxygen

will decrease and species like trout may not survive.