Natural Communities of the Mountain StateBy Jim Vanderhorst West Virginia is green. If you fly across the state in summer and look down you will be impressed by the sea of green forests that cover a large part of the landscape. Only a few states have a greater proportion of forested land. These forests are dotted and crisscrossed by the workings of humans, but it remains easy to imagine that much of our state is a truly wild and wonderful place where nature flourishes.

For a small state, West Virginia has a great diversity of natural community types. This can be attributed to its geographic spread and geologic and topographic variation. Prevailing winds traveling eastward across the state first cross a section of low hills eroded from nearly horizontal layers of rock. These lowlands support extensive deciduous forests of oaks, hickories, maples, beech, tulip poplar and other trees. The species composition of these forests varies subtly depending on which direction the slope faces, slope position (whether the forest is high or low on the slope), geologic substrate, and disturbance by humans and natural forces. Moving east the hills become bigger. As the uplifted Allegheny Mountains are approached, climatic effects of elevation become dominant influences on vegetation composition and structure. The west sides of the mountains receive the highest rainfall in the state and support some of our most productive forests. Great rhododendron, our state flower, often forms impenetrable thickets in the forest understory . Vegetation at the highest elevations often resembles that found at lower elevations further north. Here we find forests dominated by yellow birch, cherry, hemlock and red spruce. Open communities in the highlands, including rock outcrops, heath grasslands and bog-like wetlands, are some of our state's most visited scenic attractions. The Allegheny Front is the eastern continental divide. West Virginia waters to the west of the divide flow into the Gulf of Mexico, while those on the east flow into the Atlantic Ocean. These rivers and streams long ago created the dramatic landscape of gorges and valleys that we see today. Waters on each side of the divide support distinct aquatic communities, including many native species of fish, crayfish and mussels found on one side but not the other. Riparian vegetation, plants found along waterways, is some of the most diverse in the state. The timing, duration and energy of floodwaters determine what kind of vegetation can develop and persist. These types range from tall grass prairies and battered woodlands along high-energy rapids to floodplain forests and backwater swamps along slower reaches. East of the Allegheny Front, the landscape and vegetation patterns shift again. The climate is dryer and hotter. Pine trees are more abundant compared to most other parts of the state. Folded and faulted geologic layers have eroded to form parallel ridges and valleys, exposing different rock types that support contrasting vegetation. Open shale barrens, and limestone and sandstone glades occur on hot, dry southern slopes that cannot support forests. These sunny habitats host many rare and distinctly Appalachian plant species and a high diversity of butterflies. Exposures of limestone provide the conditions necessary for development of underground caves that support communities of bats and other strange animals and microbes adapted to life in the dark. No plants can grow here, however. Above ground, limestone geology is associated with gentle topography and soil fertility, which has resulted in a large proportion of natural vegetation being converted to agriculture. The easternmost part of the state's proximity to large urban populations is resulting in rapid disappearance of all types of natural communities due to residential and commercial development. These are some of the major geographic patterns of natural diversity across our state, but within these ecological regions, smaller scale patterns repeat themselves. Community types that are prevalent in one area may occur as rare patches in another area. Hollows surrounded by steep hills may stay cold enough to host plants usually found farther north in the country. Sorting out these patterns at different scales is a complex task.

Over the last decade the West Virginia Natural Heritage Program has collected vegetation data from over 1,000 plots spread across the state. Much of this work has been accomplished in partnerships with other state and federal agencies and private organizations and individuals. But much more work is needed to fill the gaps. One contribution will come from a two-year project funded by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. Just starting out, the goal of this project is to sample and classify the high elevation wetlands of the Allegheny Mountains. We will consider funding smaller projects through our research grants program to map and/or classify vegetation of specific areas or ecological systems. We hope to integrate data from other research programs when it meets minimum standards useful for classification. We will continue to work with private landowners to identify and sample high quality natural communities on their properties, especially in areas of the state where public lands are underrepresented. We will also continue to collect data from our public lands. This accumulating plot data will form the basis for a state vegetation classification and will provide data for ongoing refinement of a National Vegetation Classification, part of an International Classification of Ecological Communities. These classifications will provide a framework for effective conservation of biological diversity. By applying a consistent classification of natural communities, we can begin to address questions of rarity and imperilment of individual types. We can compare the quality of individual occurrences of each type and use this information to help make choices concerning what to conserve and where to conserve it. Jim Vanderhorst is the state ecologist stationed in Elkins . |

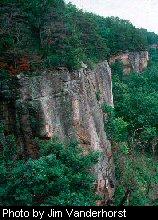

Extensive forests, small openings, wetlands, streams, cliffs and caves are all natural communities. Natural communities are groups of organisms, including plants, animals, fungi and microbes, which live together in a particular environment.

Extensive forests, small openings, wetlands, streams, cliffs and caves are all natural communities. Natural communities are groups of organisms, including plants, animals, fungi and microbes, which live together in a particular environment.  The West Virginia Division of Natural Resources Natural Heritage staff are developing a classification of the state's natural communities to help focus and prioritize conservation efforts. We start by dividing natural communities into three main groups: terrestrial, aquatic, and subterranean. Terrestrial communities are the most extensive group and are the main focus of this article but each of these three systems is a vital component of our overall biological diversity. To classify terrestrial communities, we use vegetation because plants are the least transient, the most easily studied, and the dominant life form in these systems.

The West Virginia Division of Natural Resources Natural Heritage staff are developing a classification of the state's natural communities to help focus and prioritize conservation efforts. We start by dividing natural communities into three main groups: terrestrial, aquatic, and subterranean. Terrestrial communities are the most extensive group and are the main focus of this article but each of these three systems is a vital component of our overall biological diversity. To classify terrestrial communities, we use vegetation because plants are the least transient, the most easily studied, and the dominant life form in these systems.