What's Out There?By Brian McDonald and Rose Sullivan

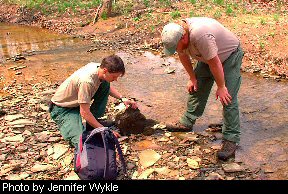

The biologists of the Wildlife Resources Section collect a lot of this data themselves, but much information is supplied by other state and federal agencies, contractors, university researchers and ordinary people with an interest in natural history or conservation. These records and observations are added to a growing database of computer and manual files at the DNR Elkins office. The West Virginia Natural Heritage Program uses this information to assess the status of the species and ecological communities and to determine which are in greatest need of conservation. We currently consider about 800 species of plants and animals of sufficient rarity that individual occurrences of these species are tracked. Our database contains about 5,000 occurrence records. This information is useful to researchers, educators and land managers who work to pass on our wealth of native species and ecological communities to future generations. Under State Code 20-2-1 , the Wildlife Resources Section is directed to protect wildlife within the state. “It is declared to be the public policy of the state of West Virginia that the wildlife resources of this state shall be protected for the use and enjoyment of all citizens of this state. All species of wildlife shall be maintained for values which may be either intrinsic or ecological or of benefit to man.”

To determine which species are of possible conservation concern, we must first know which species occur in the state and then assess which are rare. How are we doing with this task? Vertebrates, animals with backbones, are the best-documented group of wildlife, but even here several species previously not known from the state have been found in recent years. These include a fish called the bigeye shiner, the Black Mountain and Shenandoah Mountain salamanders, a lizard called the six-lined racerunner, and possibly a new breeding bird called the clay-colored sparrow. A bonus from inventory work is the publication of books, under the guidance of the Wildlife Diversity Program, on the birds, reptiles and amphibians, and fishes of West Virginia . A book on mammals is being written. In contrast to the vertebrates, the invertebrates are poorly documented. Numbers of species in some of the better known groups are shown in the table (shown below) . Our understanding of the distribution of showy groups, like the dragonflies and damselflies, is sketchy at best. Last year the Dragonfly Society of the Americas spent just one week in the state and found eight species not previously documented! Butterflies are probably the best-known group, but we need a better understanding of the status of individual species. We have little knowledge of the occurrence and distribution of the thousands of other insects across the state. DNR personnel have produced publications on mushrooms, butterflies and tiger beetles. A book on the state's freshwater mussels is nearing completion. While plants are not specifically mentioned in the mission of the Wildlife Resources Section, one cannot conserve the animals without a thorough understanding of the habitats in which they live. We do not want to harm any rare plants with our management, so we must know which species are rare and where they occur. The animals, plants and the non-living portions of the environment — soils, climate, and water for example — exist as ecological communities. Ultimately the conservation of the state's biota requires the conservation of multiple examples of all the ecological communities. Publications resulting from botanical and mycological work include checklists of the mosses and liverworts, an illustrated guide to lichens, and a recently published book on the mushrooms. A checklist and atlas of the vascular plants is nearly complete. With a recently compiled list of herbarium specimens (dried and pressed plant specimens) from several college and university collections in hand, we find that there was a peak in collections in the 1930s and another in the 1990s. The WVU Biological Expeditions, responsible for the 1930s surge, consisted of professors and students who piled into cars and spent summers camping while collecting plants across the state. Dr. James G. Needham of Cornell University served as a professor with the expedition alongside WVU Professor P. D. Strausbaugh who started the trips in 1926. Dr. Needham stated in a 1931 article in American Forests, “We gathered thousands of specimens, accounts of which will appear in scientific papers for decades to come – specimens of plants ranging from oaks to algae…and we saw life in action everyday.” Plant collecting decreased in the following decades until the 1990s when William Grafton from WVU Cooperative Extension almost single-handedly boosted collections to numbers surpassing that of the 1930s.

As a result of these collections, we know that there are 2,345 species documented from the 55 counties and represented by over 80,000 herbarium specimens. Only about 14 percent of these specimens have been collected in the last 15 years, leaving questions about the current distribution of our plants. In 2002, botanists from the Natural Heritage Program inventoried Chief Cornstalk Wildlife Management Area and Panther State Forest in the under-studied southwestern part of the state. Several trips were taken to each area in April, July and September. An effort was made to survey for plants in all the various ecological communities. From this limited effort, 304 vascular plant species were listed at Cornstalk and 371 at Panther. A large percentage, 44 percent and 27 percent respectively, had not been documented from their counties previously. With a relatively small effort put into these Mason and McDowell county surveys, we were able to demonstrate how poorly known the flora is in that part of the state. To truly understand not only the distribution but also the status of the various species across the state is a monumental task that will require a concerted effort of many partners, over many years. Large-scale biological surveys like those of the 1930s have not been reproduced in recent decades. Despite the array of modern tools such as the use of global positioning satellites and computers, only by getting knowledgeable individuals into the field will we gain a better picture of our state's biota. The Division of Natural Resources cannot accomplish this task without considerable assistance. This is where you come in! Historically, there have been some great amateur biologists whose work has proved invaluable. If any group or individual would like to assist in plant or animal surveys in any part of the state, please contact the Natural Heritage Program by writing to P.O. Box 67 , Elkins , WV 26241 or email: bmcdonald@dnr.state.wv.us . Brian McDonald is a willdife biologist and Natural Heritage Program leader. Rose Sullivan is the DNR's WildYards program coordinator. Both are stationed in Elkins. |

Ever wonder where the media gets all its information on the distribution of animals and plants in West Virginia ? Is the six-lined racerunner only found in Morgan County ? Where is running buffalo clover growing? Who is documenting the pale, wet, little cave creatures that most of us will never see? Who knows the answers to these questions? The Natural Heritage Program of the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, that's who.

Ever wonder where the media gets all its information on the distribution of animals and plants in West Virginia ? Is the six-lined racerunner only found in Morgan County ? Where is running buffalo clover growing? Who is documenting the pale, wet, little cave creatures that most of us will never see? Who knows the answers to these questions? The Natural Heritage Program of the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, that's who.  The Natural Heritage Program started cataloging the state's native species in 1975. In the early 1980s the Nongame Wildlife Program, now called the Wildlife Diversity Program, was initiated and since then the two programs have worked together on the inventory of the state's plants and animals. The primary purpose is conservation. The threat to many of our rare species is simply that their habitat is limited within the state. When plants or animals are restricted to certain areas of the state or their numbers are low, they are considered rare. Those found to be vulnerable because of very small populations or identified threats become top priorities for our conservation efforts.

The Natural Heritage Program started cataloging the state's native species in 1975. In the early 1980s the Nongame Wildlife Program, now called the Wildlife Diversity Program, was initiated and since then the two programs have worked together on the inventory of the state's plants and animals. The primary purpose is conservation. The threat to many of our rare species is simply that their habitat is limited within the state. When plants or animals are restricted to certain areas of the state or their numbers are low, they are considered rare. Those found to be vulnerable because of very small populations or identified threats become top priorities for our conservation efforts.