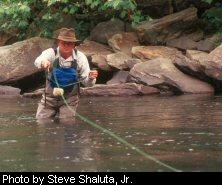

The Dream StreamBy Dan Cincotta

The answer to a West Virginian who loves our put-and-take trout program may be that it is an accessible, wide stream with big, open pools and no snags. To the purist, it may be a nearly inaccessible, boulder-strewn mountain stream with logjams, undercut banks and a heavy forest canopy. Most anglers would probably add that they would prefer their special stream to have at least one trout in every pool and nary a person in sight. Regardless of your feelings about how the perfect trout stream should look, in biological terms certain ingredients are critical for an eastern stream to support a quality trout population. Water quality, food, substrate and cover are important parameters often discussed by biologists. These terms are too simplistic, however, because they are actually only parts of an interrelated ecological and biological web that produces a high-quality trout stream. Let's try refining our understanding by examining the primary elements as they relate to West Virginia's trout populations that are mixes of the native brookie , the rainbow from the western United States and the European brown trout. Water quality is the term used to describe the chemical quality and temperature of water. Although many parameters can be measured to evaluate the quality of water, it is usually the high and low temperature, the level of oxygen, pH (an indication of acidity or alkalinity) and turbidity that make-or-break a trout stream. Trout usually thrive in water temperatures between 50 and 75 degrees and generally die at temperatures above 75 degrees. Within this range, however, the temperature which individual species prefer varies considerably. For example, the brown trout prefers 65 to 75 degrees for most of its activities, while the brook and rainbow trout become stressed above 70 degrees. These two species flourish when water remains between 55 and 68 degrees. Needless to say, temperature is critical to the success of trout. Another equally important factor, and one directly related to temperature, is the amount of available dissolved oxygen. Cold to cool water, with lots of oxygen, is a prerequisite for trout streams. In Appalachia, poorly oxygenated spring water supplies most of the cold water, usually 48 to 54 degrees, for our trout streams. This differs considerably from the snow melt sources of western streams. Assuming it's fairly clean, springwater will capture considerable oxygen as it tumbles down high-gradient mountain streams. This phenomenon occurs because cold water can capture oxygen more quickly and hold more oxygen than warm water. These high levels of oxygen are basic to keeping trout alive, sustaining growth, maintaining egg health until hatching, and supporting the aquatic insects which are a major food source for trout. Thus, to sustain a quality trout population, cold to cool stream temperatures with plenty of oxygen must be available throughout the year.

Unfortunately, the headwater mountain streams where trout live usually have the lowest acid-buffering capabilities. Natural pH values here normally fall below the neutral 7.0. Most fishes, including trout, are generally not seriously affected by a pH between 6.0 and 7.0, but, as values dip below 6.0, problems with all streamlife become noticeable. As acidity increases, the food base dwindles, and spawning success and egg survival of fishes decline. In fact, if the pH declines below 5.0, just about all species of aquatic plants and animals die. Our native brook trout has adapted to the natural infertile conditions, but even it cannot survive acid water from some mines or from acid rain. Turbidity is the term biologists use to describe the clarity of water. Land disturbances such as mining, timbering and construction can disturb stable soils and cause sedimentation, which we see as turbid or muddy waters. Sedimentation may disturb fish feeding and spawning, raise water temperatures and affect the food base. Because trout depend on sight to find their food, trout are hindered in severely turbid conditions. Even worse, food becomes scarce or disappears during extended periods of land disturbance because aquatic insects such as mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies are extremely sensitive to fine sediments. Turbid waters also reduce productivity because heavy sedimentation literally smothers eggs. To aggravate this dismal situation, muddy streams increase water temperatures and decrease energy production in plants. Hence, muddy waters are very stressful for aquatic communities. Stream bottom, or substrate, conditions are included as essential components of a healthy aquatic community because they serve as the primary habitat for most streamlife . For trout, rock and gravel substrates are needed for trout egg incubation. Trout deposit and fertilize their eggs over gravel substrates in the fall or winter. The eggs settle between the gravel and the young hatch in spring. This egg-holding area must be free of smothering silt and sediment to allow the incubating eggs to “breathe” and newly hatched young to swim up through the gravel. Small rocks in the substrate provide habitat for food-chain animals including aquatic insects, crayfish, salamanders, non-game fishes and animals. Thus, the most productive areas of streams are the clean-swept rocks and gravel of runs and riffles. The last ingredient in the natural environment's recipe for a good trout stream is cover. This term relates to any feature in or near the stream that provides fishes, adults as well as young, a place to hide and rest. For some fishes, cover may even be needed for spawning.

Water quality, food, substrate and cover — those are the basic considerations in the making of a “dream stream” for trout. But there are other factors not discussed here, and surely there are many “pathways” in the web of stream ecology that we don't understand or haven't even discovered. We do know, however, that flowing water resources are complex systems, and that the disruption of a single “pathway” can harm or eliminate a healthy trout population. If you care about trout streams and trout fishing, become involved in programs that protect and manage this resource for you and your children's long-term enjoyment. Dan Cincotta is a DNR aquatic biologist stationed in Elkins . |

Fishery biologists are often asked some tough questions about West Virginia's aquatic resources. Sometimes it's difficult to provide a straightforward reply when there isn't a textbook answer. “What makes a good trout stream?” falls into the tough category and typically generates a plethora of responses.

Fishery biologists are often asked some tough questions about West Virginia's aquatic resources. Sometimes it's difficult to provide a straightforward reply when there isn't a textbook answer. “What makes a good trout stream?” falls into the tough category and typically generates a plethora of responses.  How does the cryptic “pH” affect a trout stream? Water with a pH of 7.0 is considered neutral; anything lower is acid, and anything higher is alkaline. With this in mind, remember that many of the central Appalachian mountain soils originate from acid sandstone. This fact translates into infertile streams with water pH readings between 7.0 and 5.5, because the soils lack alkaline nutrients and minerals to buffer the water. This poor buffering capacity makes many of West Virginia streams extremely sensitive to any outside acid sources and limits the potential for aquatic productivity. Although some acid additions may come from natural sources, such as bogs, most of the state's increasing acidic water quality problems are caused by acid mine drainage and precipitation.

How does the cryptic “pH” affect a trout stream? Water with a pH of 7.0 is considered neutral; anything lower is acid, and anything higher is alkaline. With this in mind, remember that many of the central Appalachian mountain soils originate from acid sandstone. This fact translates into infertile streams with water pH readings between 7.0 and 5.5, because the soils lack alkaline nutrients and minerals to buffer the water. This poor buffering capacity makes many of West Virginia streams extremely sensitive to any outside acid sources and limits the potential for aquatic productivity. Although some acid additions may come from natural sources, such as bogs, most of the state's increasing acidic water quality problems are caused by acid mine drainage and precipitation.  Some of the more obvious cover types are large boulders, deep pools, and fallen trees. Other features that may go unnoticed or seem unimportant to the average person are the forest canopy, overhanging shrubs, submerged logs, undercut banks and aquatic plants. As you might have guessed by now, many components of this part of the web serve more than one purpose in a stream ecosystem. For instance, the forest canopy not only filters the sun's hot rays and provides shadows, it also contributes leaves for stream nutrition and terrestrial insects for food. The fallen trees, submerged logs and branches break down contributing food, nutrients and habitat for aquatic insects and other invertebrates and small fishes. The aquatic plants may be great places for gamefish to feed on hiding critters, but they are probably more important for their role in producing oxygen and food for the stream ecosystem. A diversity of cover types will benefit any stream system.

Some of the more obvious cover types are large boulders, deep pools, and fallen trees. Other features that may go unnoticed or seem unimportant to the average person are the forest canopy, overhanging shrubs, submerged logs, undercut banks and aquatic plants. As you might have guessed by now, many components of this part of the web serve more than one purpose in a stream ecosystem. For instance, the forest canopy not only filters the sun's hot rays and provides shadows, it also contributes leaves for stream nutrition and terrestrial insects for food. The fallen trees, submerged logs and branches break down contributing food, nutrients and habitat for aquatic insects and other invertebrates and small fishes. The aquatic plants may be great places for gamefish to feed on hiding critters, but they are probably more important for their role in producing oxygen and food for the stream ecosystem. A diversity of cover types will benefit any stream system.