West Virginia's Dirty DozenBy Emily Grafton

What makes a plant an exotic species? An exotic plant has been transplanted from its habitat of origin to another one, like when a person has moved from one culture or country to another. Exotic species may be transplanted from other countries or from the eastern United States to the west, or vice versa. The seeds of exotic plants disperse in all directions, even making their way into wilderness areas on the boots of hikers, on vehicle tires, or the fur of animals. Over eons, native plant species co-evolved with native animals from the largest mammal to the tiniest microorganism. Through time and their dynamic struggle for survival, organisms living within a given habitat form interdependent roles, or niches. Natural checks and balances also evolve which prevent the population of any one species from overtaking the plant community, or eating itself out of house and home. For example, most of the butterflies gracing our landscape rely on specific native plants during a part of their life cycle. In fact, most insect species require a range of native plant species for food at some point in their lives. Birds and other animals feed insects to their young. These biological interconnections continue throughout the web of life within an ecosystem. When a plant from one ecological system finds its way into another, the intruder may develop a competitive edge. It may have little susceptibility to diseases within its new environment. If other conditions are favorable, the alien plant may invade the existing community. Why does a given plant species become invasive? The growth and distribution of any living organism is a complex process; however, two primary factors seem to contribute interchangeably to plant invasions. These are the biology of a plant species and disturbances to the land. Disturbances to the landscape such as roads, gas and power line rights-of-way, mining and housing developments often take ecological succession back to the first stage–bare ground. This creates opportunities for these plants to become established. Once established, their rapid growth and reproduction rates allow them to cover and choke out native plant communities. Disturbances in natural areas such as overgrazing by deer may create opportunities on the forest floor for invasive species populations to expand. Once established invasive species prevent the once diverse carpet of wildflowers from returning. As a result of the introduction and spread of invasive species, increasing losses of wildlife food and habitat occur. In addition, it costs billions of dollars to protect and restore natural resources threatened by invasive exotics. The spread of invasive species has exploded over the past few decades. What may seem to be the most problematic species today, may change over the next few years, as you will glean from the examples below. 1. KUDZUImagine a half-mile stretch of a southern West Virginia hillside wearing a ruffled-green cloak, bumpily draped over poles of varying heights. A successful invasion of a creeping vine called kudzu ( Pueraria montana ) looks eerily like this. Forget the trellis. This vine grows a foot a day, extending nearly 60 feet in a growing season over shrubs and trees, strangling branches and smothering foliage. Within a few years, acres of wildlife habitat vanish. Kudzu was introduced to the U.S. from Asia in 1876 and promoted as a forage crop for livestock and as an ornamental plant. Beginning in the 1930s it was promoted as a control for soil erosion. By 1953, it was considered a weed pest or “weed gone wild.” 2. WATER SHIELDWater shield ( Brasenia schreberi ) first appeared in a lake in West Virginia about 3. CROWN VETCHCrown vetch ( Coronilla varia ) was introduced from Asia in the 1950s for use as a ground cover for erosion control on roadsides and excavation sites. This aggressive plant invades sunny habitats, climbing over small trees and ground cover and shading them out. Rodney Bartgis , director of the Joint Central Appalachian Program of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) directs a program to combat invasive exotics. He points out that plants like crown vetch threaten several state and globally rare species on TNC preserves. 4. JAPANESE KNOTWEEDJapanese knotweed ( Polygonum cuspidatum ) entered the United States from Asia in the late 1800s and has become one of our state's most widespread and problematic invasives . It thrives in riparian habitats, completely covering miles of stream banks. Patty Morrison, a botanist with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Ohio River Islands National Wildlife Refuge, says that Japanese knotweed dominates nearly 600 acres on the islands. 5. JAPANESE STILTGRASSJapanese stiltgrass ( Microstegium vimineum ) is the plant Bartgis would place at the top of the list for threatening forest understory habitat . Japanese stiltgrass was used as a packing material in boxes of porcelain imported from China in the early 1900s, and probably escaped into the wild as people disposed of the dried grass. It easily invades habitats that have been disturbed by roads and trails, displacing wetland and forest understory vegetation. It can completely displace hundreds of species of wildflowers and prevent the growth of tree and shrub seedlings. 6.GARLIC MUSTARDGarlic mustard ( Alliaria petiolata ) poses threats to native plants and animals in forest communities. The two- to three-foot high plants invade the forest floor much like Japanese stiltgrass . Garlic mustard and Japanese stiltgrass outcompete native plants by monopolizing light, moisture and nutrients. Insects and small mammals depend directly on seeds, foliage, nectar and fruits of hundreds of species of native herbaceous plants. Larger mammals depend on the smaller ones for food. Consequently, just one invasive species like garlic mustard may displace a whole ecosystem. 7. TREE-OF-HEAVENTree-of-heaven ( Ailanthus altissima ) ranks as one of the most significant threats “Tree-of-heaven produces as much as eight feet of growth in one year,” says Bill Grafton with the West Virginia University Extension Service. Like the famed Hydra of Greek myths, you cut a tree-of-heaven down and it sprouts multiple new “heads” from its roots. Very few native tree species sprout new stems from their root systems. Consequently, loggers need to avoid cutting this tree without applying a herbicidal treatment to kill the root system. Leaving a few cut trees in a forest or near a forest edge may lead to a rapid displacement of the existing forest that was once there. 8. REED CANARY GRASSReed canary grass ( Phalaris arundinacea ) is a large, sod-forming grass that escaped from cultivated fields into wetlands across the state. In Canaan Valley and the wetlands of many of our state wildlife management areas, reed canary grass has taken over hundreds of acres of wetland habitat. It has very little wildlife value except for cover. Where it thrives, it displaces the diversity of native plants that provide food for waterfowl and serves as host plants for insects eaten by birds and other animal species. 9. MILE-A-MINUTEMile-a-minute weed may grow faster than tree of heaven, producing as much as ten feet of growth in a year. This trailing vine grows over shrubs and trees blocking sunlight, severing the lifeline of sunlight to every plant under it. Distributed mostly along the Ohio River, it poses serious problems on the Ohio River Islands National Wildlife Refuge. It readily invades open areas such as streambanks , parks, roadsides and forest edges. 10. PURPLE LOOSESTRIFEPurple loosestrife ( Lythrum salicaria ) has become the “poster child” for invasive species across the nation. This four- to ten-foot high perennial produces beautiful spikes of rose to purplish colored flowers. It thrives in a variety of wetland habitats, displacing the native grasses, sedges and other flowering plants beneficial to wildlife. It has destroyed thousands of acres of wetland habitat in the U.S., but currently has a restricted range in West Virginia. It may become a major problem, however, as people still buy this plant as an ornamental. 11. MULTIFLORA ROSEMultiflora rose ( Rosa multiflora ) long ago surpassed the qualifications as the most problematic invasive plant species, however, its prolific spread across fields, 12. YELLOW IRISWho does not love the beauty of an iris? The elegant yellow iris ( Iris pseudoacoris ) may be beautiful, but its escape from cultivation is anything but. This native of Europe thrives in the open water of wetlands. Just thirty years ago, it existed in fewer than six counties, now it may be found throughout 20 counties. It is spreading like a hurricane through a Canaan Valley State Park bog, threatening to degrade the productivity of this habitat for wildlife, and eliminate several species of rare plant species including one of two existing populations of showy lady slipper ( Cypripedium reginae ). Emily Grafton was firmerly the DNR's Wildyards Coordinator.

|

Within the past few decades a new biological pollutant has reared its ugly head, threatening the health and productivity of our native ecosystems. Organizations with names like Weed Warriors and Weed Busters have declared war against this seemingly benign enemy -- plants. Citizen volunteers and professionals alike have armed themselves with every garden tool imaginable to literally “root out” invasions of exotic plant species.

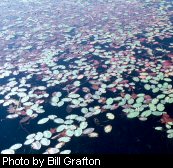

Within the past few decades a new biological pollutant has reared its ugly head, threatening the health and productivity of our native ecosystems. Organizations with names like Weed Warriors and Weed Busters have declared war against this seemingly benign enemy -- plants. Citizen volunteers and professionals alike have armed themselves with every garden tool imaginable to literally “root out” invasions of exotic plant species.  30 years ago. This small, lovely waterlily produces rounded-purplish leaves and purple flowers. Water shield now occurs in bodies of water across the state including Pendleton Lake in Blackwater Falls State Park. Water shield has out competed native aquatic plants and its thick growth interferes with fishing lines and the movement of paddleboats. The lake was drained this winter with the objective of killing the plant.

30 years ago. This small, lovely waterlily produces rounded-purplish leaves and purple flowers. Water shield now occurs in bodies of water across the state including Pendleton Lake in Blackwater Falls State Park. Water shield has out competed native aquatic plants and its thick growth interferes with fishing lines and the movement of paddleboats. The lake was drained this winter with the objective of killing the plant.  to timberland in the state, already invading thousands of acres of forestland. Once established, it forms impenetrable thickets and prevents native trees from growing back.

to timberland in the state, already invading thousands of acres of forestland. Once established, it forms impenetrable thickets and prevents native trees from growing back.  parklands and woodlands placed it on the state's noxious weed list. In the early 1930s scientists promoted multiflora rose for use in erosion control and as a living fence for livestock. Birds relish multiflora rose berries and inadvertently deposit the seeds across the state. Multiflora rose supports fewer numbers and kinds of wildlife species because it does not provide adequate food and cover for all species. Hundreds of thousands of dollars are spent each year trying to remove this pest plant.

parklands and woodlands placed it on the state's noxious weed list. In the early 1930s scientists promoted multiflora rose for use in erosion control and as a living fence for livestock. Birds relish multiflora rose berries and inadvertently deposit the seeds across the state. Multiflora rose supports fewer numbers and kinds of wildlife species because it does not provide adequate food and cover for all species. Hundreds of thousands of dollars are spent each year trying to remove this pest plant.