The Moundbuilders By Dan Cincotta and Stuart Welsh The moundbuilders? I know what you're thinking. This story must be about the Adena Indians who lived in the Ohio River Valley and buried their deceased loved ones in mounds. But, you are so wrong! This story is about another native West Virginia group that builds mounds every year during springtime, and that probably built mounds thousands of years before the Adena Indians ever did. These mounds, however, are not used to bury the dead, but to spawn a new generation of life. The group that still practices this painstaking activity, believe it or not, is a group of fishes -- minnows to be more specific! Most minnows are not moundbuilders. The minnow family (Cyprinidae) includes more than 2000 species worldwide and more than 250 species in North America. Less than 10 percent of North American minnows construct mounds, which are used as spawning nests. In West Virginia waters, spawning mounds are built by three groups of minnows. The first group includes bigmouth, bluehead, hornyhead and river chubs in the genus Nocomis. Although only one species is officially called a “hornyhead,” most mound-building minnows have “horns” during the spawning season. The fallfish (genus Semotilus ) is the second group of moundbuilders, and represents the largest native minnow in the mountain state, often growing to a length of 18 inches. The third mound-building group (genus Exoglossum ) includes two species commonly called cutlips minnows, named after a unique protruding lower lip. The three groups of mound-building minnows, usually ranging from 3 inches to 18 inches when sexually mature, are collectively called chubs, owing to their “cigar-shaped” bodies. For the spring spawning season, the heads of most mature male moundbuilding chubs develop breeding tubercles, also called “horns” or pearl organs. These horns are not always restricted to the heads of males, but in some species are found on the body and fins of both sexes. Horns are deciduous, and shed after the spring spawn. Horns on the head of chubs possibly play roles in nest defense and stimulation of mates. Body tubercles may assist in maintaining contact between spawning individuals.

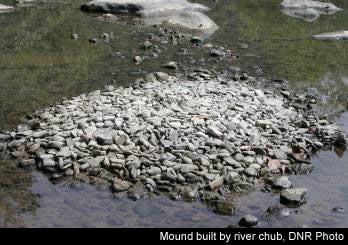

Let's focus on “how” and “why” minnows make mounds. During the first spring of sexual maturity, male fallfish and chubs in the genus Nocomis initiate spawning by excavating a pit on the stream bottom. They do this by nudging and pushing the stones with their heads, or carrying them in their mouth one at a time. Next, the male selects and totes stones with his mouth and stacks the stones back into the pit he excavated during a two- to four-day period. After completion, the mound created may contain thousands of similar-sized stones. Larger chubs move larger stones and make larger mounds. The somewhat-circular mound of a large fallfish can measure up to six feet in diameter and three feet in height. Spawning occurs in or over a trough on the side or top of the mound. Interestingly, chubs are not the only users of these mounds. Since small stones are not in abundance in some West Virginia streams, many other minnow species use this prime spawning real estate for their own reproductive activities. Spawning rituals are generally similar among the chub groups. In the case of the widely distributed river chub of the genus Nocomis, the male moves into or over the trough and trembles, thus sending sexual signals to the female. Next, the female swims to the side of the male and deposits her eggs. The release of eggs and sperm takes about a second and usually occurs multiple times in succession. The female fallfish may release between 1,000 to 12,000 eggs. The smaller Nocomis chubs and cutlips minnows release only 250 to 750 eggs. Timing is critical for stream-spawning minnows, because fertilization occurs externally in flowing water. After spawning, males cover the pit and eggs with stones, presumably to prevent predation of eggs and suffocation of the eggs by silt.

The cutlips minnows can only transport pebbles because of their unique protruding lower lip. As a result, cutlips minnows build smaller nests than those of fallfish and Nocomis chubs. Also, unlike other moundbuilders, cutlips minnows do not create a pit prior to moundbuilding, nor do they construct a spawning trough on the upstream side of the mound. In all of these species, eggs incubate about 10 to 14 days before hatching. As you've read this intriguing story, you might have remembered times when you have seen piles of stones of the same size that stood high and dry above low summer flows. You probably pondered how those stones came to be piled in one spot. Now you understand why the Native Americans of the Hudson Bay region called the minnows “Awadosi” or “stone carriers.” Or you might have thought about catching funny looking fish with “horns” while fishing in a riffle or pool. Perhaps you already had your own name for these unusual fishes, just as the Indians in the Tennessee region did when they called these chubs “Ugunsteli,” meaning the “horned fish.” Needless to say, some unique fishes inhabit the Mountain State . For the most part, we are lucky that chub species are still found in state waters, given previous periods of poor water quality. As our population grows within West Virginia and around the country, we must implement plans to protect and manage our water resources. We must not take our aquatic life for granted, as it is one of the most jeopardized faunal groups in the country. With the enforcement of current water laws and the implementation of watershed management strategies, we will be able to enjoy these intriguing fishes and their special life habits for years to come. Dan Cincotta is a wildlife fisheries biologist stationed in Elkins. Stuart Welsh is a professor at WVU. |