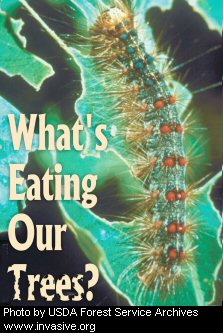

What's Eating Our Trees?By Nanci Bross-Fregonara

A recent forest inventory report published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service and the West Virginia Division of Forestry shows an alarming new trend: West Virginia's trees are nearly as likely to die from disease, pests and fire as they are to be harvested for timber. This trend could decrease shade for trout streams and threaten the food supply of the Mountain State's wildlife. West Virginia University Extension Service Wildlife Specialist Bill Grafton says that a wide variety of animals use trees as sources of food. Deer, bear, squirrel and turkey rely heavily on acorns from oak trees. Maples, hickories and black cherry also provide food for wildlife. Grafton particularly worries about the deer herd. “The deer herd in some northern counties is well above carrying capacity,” says Grafton . “Browse in the woods is getting pretty scarce. When there's not enough food in the woods, they wind up moving closer to roads and gardens.” Dick Hall, Division of Natural Resources game management supervisor, agrees. “For this reason, it is important to harvest an adequate number of antlerless deer each year,” he says. One of the most well-known culprits in this forest loss is the gypsy moth that targets the state's hardwoods. State Forester Randy Dye points out that the annual tree mortality – roughly 138 million cubic feet – represents more than half of the total volume of trees harvested annually. Many of those are oaks, which can bring as much as four times more at market than other trees. “West Virginia is the number two producer of hardwood growing stock in the nation, and about 70 percent of the state's acreage is populated with oak species,” says Dye. The gypsy moth has taken a substantial toll on the oaks, however, cutting into mast production for deer and a variety of other wildlife in the process. While the West Virginia Department of Agriculture's Plant Industries Division has been battling the gypsy moth for nearly 25 years, another insect is on the attack. The hemlock woolly adelgid literally saps the strength out of hemlocks, trees known for providing summertime shade for streams containing heat-sensitive trout. Within the past 10 years, the pest has moved into the state's eastern border counties and shows continued southern and westward movement. The adelgid secretes a waxy, woolly-looking residue as it feeds on sap from the tree and can kill the tree within four years of infestation. The adelgid has infested hemlocks in 18 counties in West Virginia. The infestation is found in Greenland Gap The damage is significant, for when a hemlock stand dies, the local microclimate changes significantly, with higher temperatures and lower humidity affecting other species that may live there as well. “The evergreen canopy of hemlock affects light, temperature and humidity levels in the understory ,” says Jim Vanderhorst , DNR ecologist. “Hemlock forests are a contrasting habitat to the predominately deciduous forests in West Virginia. They are the preferred habitat for a number of birds, mammals and amphibians, for some or all of their life stages and seasons.” A closely related invader, the balsam woolly adelgid , is currently attacking a unique fir species found in the isolated high elevation bogs and swamps of north central West Virginia. The “Canaan Valley” balsam, thought to be a unique subspecies of its more northern cousin, is also recognized as a superior Christmas tree stock. Researcher Leah Ceperley , awarded a grant from the DNR, studied the types and health of the balsam fir communities located in the state's high elevation wetlands. “During the last decade, a decline in live mature firs in West Virginia has reinforced their imperiled status,” Ceperley notes. “The balsam woolly adelgid threatens the health and existence of the fir stands and their associated communities.” The wooly adelgid is an exotic species, brought in on nursery stock from Europe, Ceperley explains. “It has already killed most of the Fraser firs in the Smokies . European firs are naturally resistant to the insect, but North American firs are not and die quickly.” Nearly every natural stand of balsam in West Virginia has adult trees that are either dying or are already dead, at least in part because of adelgid damage, she says. “The fir communities are suffering massive death, with those affected stands highly visible because they are snags or stands of balsams with orange needles.” In 1975, one wetland was noted to have 26 percent to 50 percent canopy cover by fir trees. By 2000 that percentage had been reduced to less than 10 percent. “As This conversion is happening quickly. The balsam firs found in the Mountain State had been relatively healthy until the last decade, Ceperley points out. “Field surveys conducted in 1990 make no mention of the declining health or threats from infestation.” While she says that there has been little success with adelgid control measures on natural stands, other methods may help strengthen balsam populations. Researchers are finding that while the adelgid attacks adult trees, they seem to have less effect on young trees. Unfortunately those trees are threatened more by deer browsing. Currently personnel from the DNR Wildlife Resources Section, Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge and Canaan Valley State Park are building exclosures to keep deer from eating balsam seedlings. Ceperley says, “Overabundant deer in the Valley decimate balsam seedlings, the next generation of fir. Keeping the deer away from a few seedlings will hopefully give them a chance to grow to maturity and produce cones before succumbing to the adelgid .” She also found that some trees do not seem to be as easily killed by the adelgids , giving hope that a very small number of trees may have resistance to the insect. Another highly threatened tree species is the elegant flowering dogwood. In some areas, such as Coopers Rock State Forest, the dogwoods have been killed in a matter of only three to four years. For those familiar with the destruction caused by Dutch elm disease and with the loss of the American chestnut, this attack on the dogwood seems like a bad memory revisited. Within the last few years, dogwood The disease is caused by the fungus Discula destructiva which causes small purple leaf spots that enlarge to form large, tan spots and blotches of dead plant cells. Once it spreads onto the branches, the disease progresses rapidly, usually within three to five years after initial infection. In West Virginia, anthracnose disease is moving quickly. In a 1999 state inventory of 100 impact plots, 44 percent of the flowering dogwoods surveyed were dead. In other states the percentage is just as high, with some fear of losing all of these beautiful trees. For dogwoods in the Mountain State forests the outlook is grim. The

U.S. Forest Service is predicting 80 percent to 100 percent mortality in the National Capital Region and others predict virtual elimination for elevations above 3,000 feet. It is hard to imagine our forests without the blossoming dogwood, mighty oak or ageless stands of evergreens. The ramifications spread outward like a tree's roots. “Some of the greatest changes to our world are caused by overlooked, tiny bugs and microbes,” notes Vanderhorst . “It is often too late once we notice them.” On the radar:Sudden Oak Death: Although sudden oak death has not been identified in Appalachia, it is an important potential threat to West Virginia forests where the land area is predominantly oak forest. Sudden oak death, or SOD, is caused by the fungus Phytophthora ramorum and has killed tens of thousands of trees in California and Oregon since 1995 . Thought to have been introduced from Europe on rhododendron, SOD is a danger because it can be carried by nursery stock that is shipped all over the country. West Virginia is considered at high risk for the disease based on climate and abundance of vulnerable species, such as huckleberries, rhododendrons and azaleas, as well as red oaks. Since Douglas fir is also a host, the importation of contaminated Christmas trees is of concern. It cannot be eradicated, but efforts are underway to try to contain it to the West Coast through state and federal quarantines. The Emerald Ash Borer -The emerald ash borer is most widespread in Michigan and has moved from there to Maryland, Virginia, Ohio and Canada. It can kill ash trees in as few as two years. Eradication efforts are underway in all of these locations. Nanci Bross-Fregonara is a public information specialist stationed in Elkins . Rose Sullivan, WV DNR and Buddy Davidson, WV Department of Agriculture contributed to this story. |

Nature Preserve as well as Cathedral and Blackwater state parks, with some areas having entire stands decimated.

Nature Preserve as well as Cathedral and Blackwater state parks, with some areas having entire stands decimated.  the older canopy trees have died, the community is converting to a dominantly herbaceous cover type,” Ceperley says. “Standing snags of Canaan Valley balsam fir are all that reflect its former presence in the area.”

the older canopy trees have died, the community is converting to a dominantly herbaceous cover type,” Ceperley says. “Standing snags of Canaan Valley balsam fir are all that reflect its former presence in the area.”  anthracnose disease has had a devastating impact on flowering dogwoods throughout the state. According to the state Department of Agriculture, it is the most serious problem affecting the flowering dogwood ( Cornus florida ) in the eastern United States and is spreading rapidly, killing trees in a very short period of time.

anthracnose disease has had a devastating impact on flowering dogwoods throughout the state. According to the state Department of Agriculture, it is the most serious problem affecting the flowering dogwood ( Cornus florida ) in the eastern United States and is spreading rapidly, killing trees in a very short period of time.