Although most saw-whet owls pass through West

Virginia during migration, a small breeding population exists.

A Look At Our Smallest Owl

By Rob Tallman

Here you are, high on a mountain in the Cranberry Wilderness surrounded

by a dense red spruce forest. The sun is setting and the woods are

growing dark. The thrushes sing the last few verses of their evening

chorus and the forest around you becomes silent. The stage is set for

the long quiet night ahead.

Then, out of nowhere, just outside the light of your fading campfire;

an incessant, monotonous TOOT….TOOT….TOOT….TOOT….TOOT….TOOT….TOOT

begins and lasts for what seems like forever. You haven’t a clue

as to what’s producing this annoying noise, a sound much like

the back-up alarm on a garbage truck! After all, you’ve spent

nights in the high country, but never experienced anything such as

this. Consider yourself fortunate. You have just encountered one of

the Mountain State ’s rarest and most secretive creatures--the

northern saw-whet owl. The northern saw-whet owl is a bird of the northern

boreal forest with a relatively small but stable breeding population

extending down the spine of the Appalachians through West Virginia

and into the Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina . The

adult saw-whet’s plumage consists of a rusty-brown streaked underside

and a darker brown back and wings with white or buffy colored spots

throughout. The juvenile is mostly chocolate brown with a conspicuous

white “V” on its forehead. The plumage of both age classes

is set off by distinctive large yellow eyes.

The saw-whet’s most endearing feature is its size. It is the

smallest owl in West Virginia , weighing in at 2.6 to 3.5 ounces (75

to 100 grams), slightly larger than the American robin. Don’t

let its small size fool you, however, as it is a very efficient predator,

feeding mainly on mice as well as other small mammals. Northern saw-whet

owls are strictly nocturnal, feeding throughout the night and remaining

well hidden during the day.

Northern saw-whet owls, a cavity-nesting species, will use natural

cavities created by woodpeckers but will also use man-made nest boxes.

In West Virginia , saw-whets begin displaying courtship behavior in

early March. Typically, the female lays five or six eggs by mid-April

and incubates them for three to four weeks. In most years the young

have fledged by early June.

Unlike other common West Virginia owls, saw-whets are migratory.

Most of the eastern population (including those breeding in Canada

and the Appalachians ) winters in the southeastern United States .

In West Virginia , saw-whets begin their southward migration in early

October and may continue into early December, with the peak migration

occurring around Halloween. The spring migration is thought to occur

during February and into early March, but, as with many migratory birds,

their spring migration is much less concentrated and poorly understood.

The number of saw-whets migrating each year is highly variable and

is thought to be based on the cyclic nature of the small mammal populations

upon which they feed.

Even though considerable research has been conducted in the northern

portion of the saw-whet’s range, relatively little has been conducted

in the central and southern Appalachians . This research need is especially

important since suitable breeding habitat is restricted to high elevation

red spruce forests and migration patterns as a whole are poorly understood.

In response to this research need the West Virginia Division of Natural

Resources Wildlife Diversity Program initiated three studies to better

understand the migration patterns, breeding distribution and abundance

of the Northern saw-whet owl in the state.

The first study, initiated in 1997 through a research grant from

the Wildlife Diversity Program, established a northern saw-whet owl

fall migration banding station in  Randolph County . The station began

operations in the fall of 1997 on Shavers Mountain but was moved to

Stuart Knob just east of Elkins in 2000. More than 600 saw-whets have

been captured and banded at this station since its inception. Migrating

saw-whets are attracted using an audio lure recording of their call

set up in front of a line of nearly invisible nets, called mist nets.

The owls fly in to investigate the call and become entangled in the

nets. Randolph County . The station began

operations in the fall of 1997 on Shavers Mountain but was moved to

Stuart Knob just east of Elkins in 2000. More than 600 saw-whets have

been captured and banded at this station since its inception. Migrating

saw-whets are attracted using an audio lure recording of their call

set up in front of a line of nearly invisible nets, called mist nets.

The owls fly in to investigate the call and become entangled in the

nets.

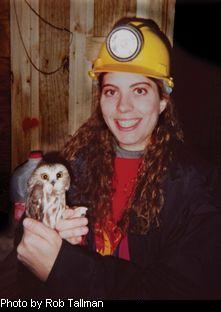

Once an owl is captured, biologists weigh the owl, measure its wings

and tail, note the eye and bill color, determine the age and sex, and

place a numbered aluminum band on its leg before releasing it. If that

owl is ever captured again or found dead, anywhere, the number on its

leg band can be traced and valuable information on migration patterns,

life span and general natural history will be gained. The Stuart Knob

banding station is one of a network of over 50 such stations across

the United States and Canada. Each fall several thousand saw-whets

are banded at these stations and many recaptures are noted, providing

key information on saw-whet behavior.

The second and third studies are designed to ascertain the distribution

and population density of northern saw-whet owls in the state. A nestbox

placement program began in 2001. To date, 135 saw-whet owl nestboxes

have been placed in appropriate habitat in Pocahontas, Randolph, Tucker

and Webster counties. DNR personnel will place another 75 nestboxes

this fall. Only three of these boxes have had evidence of breeding

saw-whets since 2001. However, given the fact that less than 12 confirmed

breeding records have ever been recorded in the state, the nestbox

program has made a significant contribution to our knowledge of the

northern saw-whet owl in West Virginia.

DNR personnel and volunteers check nestboxes each April for breeding

evidence. If a nestbox is occupied, it is revisited in May so that

both parents and young can be banded. In addition, all the same measurements

are taken as mentioned above for fall migrating birds.

The third study is an audio playback survey designed to elicit responses

from territorial breeding saw-whets in order to gain an understanding

of the distribution of breeding pairs. DNR biologists conduct these

surveys in early April when most saw-whets are highly territorial.

This is a roadside survey conducted by broadcasting the call of the

saw-whet through a loud speaker at half-mile intervals. Any territorial

saw-whet owls in the area perceive this broadcast call as another saw-whet

invading their breeding territory and respond by flying in and calling

back, occasionally even dive bombing the loud speaker! This survey

method enables DNR biologists to estimate the number of breeding pairs

in an area that otherwise would go undetected due to their secretive

nature. This is also helpful in the placement of nestboxes into appropriate

habitat.

Even though occurrences of the northern saw-whet owl are relatively

rare in West Virginia, it is likely that this species is, in appropriate

habitat, more common than once thought. However, the only way to determine

this is by way of studies currently underway. So the next time you

find yourself in West Virginia’s high country, remember to keep

an eye (or an ear) out for this small, secretive owl.

Rob Tallman is a wildlife biologist stationed in Elkins.

|

Whooooo Needs You?

The future success of these studies is largely dependent upon volunteer participation. Anyone interested in helping

conduct Northern Saw-whet Owl surveys is encouraged to contact Rob

Tallman at robtallman@dnr.gov

or (304) 637-0245. All studies are conducted in the mountain counties.

dependent upon volunteer participation. Anyone interested in helping

conduct Northern Saw-whet Owl surveys is encouraged to contact Rob

Tallman at robtallman@dnr.gov

or (304) 637-0245. All studies are conducted in the mountain counties.

Volunteers interested in the nestbox study must be willing

to hike long distances while carrying gear. Those interested

in the fall banding or playback studies can expect to be out

in the field after dark and work well into the night, often in

cold weather. |

|

dependent upon volunteer participation. Anyone interested in helping

conduct Northern Saw-whet Owl surveys is encouraged to contact Rob

Tallman at

dependent upon volunteer participation. Anyone interested in helping

conduct Northern Saw-whet Owl surveys is encouraged to contact Rob

Tallman at