Getting the Biggest Bang (or Splash) For the BuckBy Steve Brown

You take out your wallet, pull out some cash or plastic, and pay for this year’s hunting and fishing license. As you slip the new license into your wallet, you might wonder a moment about it. Why do you even have to have a license to hunt and fish? After all, you can do a lot of other fun things without any license at all. What exactly does the $33 average cost that you paid for this license actually pay for? Most importantly, what value are you getting for your money? To answer these questions, let’s step back in time a bit. When the early immigrants first came to the New World from Europe , they were seeking freedom of many sorts. It is not commonly appreciated that one of those was the freedom to hunt and fish. In Europe , hunting and fishing were exclusive rights of aristocrats, because fish and game were the property of landowners, not the property of the people. The early settlers were determined that things would be different here. Since those days, fish and wildlife in the United States have been the property of the people, no matter on whose land they might be found. Of course, different thinking about the ownership of fish and wildlife also required different thinking about their management. If the landowner privately owns the wildlife, the landowner must pay for a private “gamekeeper.” If the public collectively owns these resources, then the public must collectively pay for their management. So, historically, how have we decided who should pay and how much? Well, the answer to the “Who pays?” question didn’t exactly come right away. Things had to get pretty bad before we dealt with these issues. That happened by the beginning of the 20th century, when many fish and wildlife species had been so decimated by habitat loss and unregulated harvest that action had to be taken to restore their numbers. Unfortunately, it was too late for some species. Hunters and anglers took the lead in wildlife restoration, lobbying for the establishment of hunting and fishing licenses and, later, federal excise taxes on sporting equipment, with the revenues dedicated to wildlife management. User-supported funding of fish and wildlife management through license fees has been a tradition for almost a century now. So that is the reason we have hunting and fishing licenses, and the general answer to where your $33 goes. The current prices for resident hunting and fishing licenses were set in a bill passed by the legislature in 1988. It was strongly supported by the very sportsmen who would pay the fees. All West Virginia hunting and fishing license fees go to the Division of Natural Resources and by law must be used for fish and wildlife management principally benefiting hunters and anglers. License revenues comprise 58 percent of the total revenues available to the DNR for fish and wildlife management. Federal excise taxes are the second largest revenue source at 22 percent of total revenue. Thus, about 80 percent of the Division’s revenues come from sportsmen continuing the fine tradition of user support for management activities. Only about 5 percent of revenues for wildlife management come from state taxes. How is your license revenue spent? State law mandates that 40 percent be used for wildlife law enforcement activities, 40 percent for biological wildlife management,

10 percent for capital improvements

and land

acquisitions, and 10 percent for Division administration. Let’s

relate that to your $33 average license cost. About $12 will be

spent for wildlife law enforcement to maintain an average of two

conservation officers in each of the state’s 55 counties.

Another $12 will be spent for biological wildlife management, subdivided

as follows. About $6 is spent for hands-on management of game species

on public lands and regulatory management of game harvests on all

private lands. A comparable $5 will be spent for fisheries management

on public lakes and all of our rivers and streams, as well as the

operation of state fish hatcheries. Another $1 will be spent protecting

fish and wildlife habitat by coordinating with other agencies and

entities.

· Assurance that conservation officers are out in the field protecting your resources from those who don’t want to play by the rules. · Habitat and population management of game on 1.4 million acres of public lands and population management of game on 14 million acres of private lands across the state. · Fisheries management to provide good fishing for you and your kids in 21,000 acres of public lakes and 31,000 miles of rivers and streams. · Protection of your fish and wildlife resources and their

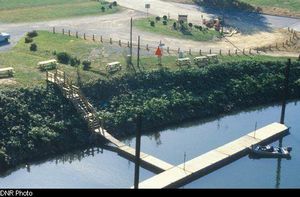

ha · Over 3,000 acres of new wildlife management areas, 12 new angler access sites, two improved rifle ranges and two new fishing lakes. Does that seem like a good value to you? When you think about it that way, I’ll bet that $33 piece of paper you just slipped into your wallet never looked like a better value. Indeed, it’s real bang (and splash!) for your buck! Steve Brown is a wildlife planner stationed in Elkins.

|

|

bitat from activities that would diminish them.

bitat from activities that would diminish them.